People’s communication is the path

It revives the conditions of social production and reproduction of meaning, and the dynamics of organization and mobilization, to instigate processes of change.

- Opinión

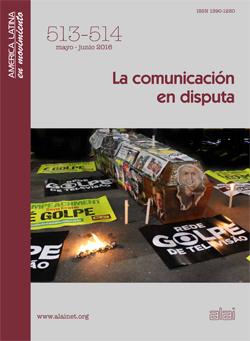

| Article published in ALAI’s magazine No. 513, 514: La comunicación en disputa 02/06/2016 |

Striking out at anything with the faintest whiff of democratizing communication – a strategic area for overcoming existing asymmetries and de-monopolizing expression in benefit of greater pluralism and diversity –appears to be one of the priorities of both the legitimate and illegitimate right-wing governments in the region.

With the stroke of a pen, on assuming the mandate in Argentina, Mauricio Macri practically wiped out the Law on Audiovisual Communication Services, with an executive decree, in order to protect the handful of media monopolies that supported his election. This law, one of the most widely discussed law bills in the history of the country, was approved in 2009 after a laborious process of civic construction with the participation of numerous social and political sectors.

In Brazil, where a palace coup is underway, driven the powers-that-be (business, media, sectors of the judiciary, police and the parliamentary right), interim president Michel Temer not only has attempted to close down the Ministry of Culture, but also to illegally intervene in the Brazilian Enterprise of Communication (EBC), created in 2007 to manage the public federal radio and television stations. In fact, this was one of the few measures adopted in this area by President Lula.

The message is clear: it is not enough to have a powerful bastion in the media; the aim is also to curb any advances (big or small) that were won in the perspective of democratizing communications. Moreover, given the anti-popular character of the policies envisaged in their neoliberal programmes, they are also attempting to eliminate any spaces of public demonstration.

A tough struggle

During the electoral campaign of 2010 in Brazil, the president of the National Press Association, María Judith Brito, bluntly pointed out: “the media have in practice assumed a position of opposition in this country since the (political) opposition is profoundly fragile”. And precisely because of this role of political hub that has been assumed by the media, the label Partido da Imprensa Golpista (PIG – or party of the putchist press) was coined. And today it is playing a key role in the coup that seeks to impose economic power over democratic decision.

This is why, last May 5, the country was the scene of diverse public demonstrations on the “National Day of Struggle against the Media Coup Plot”, to denounce “how the private communications monopoly, represented mainly by the Globo Organizations, harms our democracy, freedom of expression and the right to communicate”.

Launched by the National Forum for Democratization of Communications (FNDC) and the People’s Brazil Front (FBP), this day of struggle represents a living testimony to the dispute taking place in the field of communication in our region: that is, the aspiration of popular forces to assert the right to communicate in the face of a media structure concentrated in the hands of a few families or corporations that are attempting to define the future of our countries.

One of the changes taking place in the region is precisely the fact that the issue of regulating the media system now has a place in public debate, when it was previously regarded as unmentionable. And this is so, above all due to the revival of movements for the democratization of communication, a cause that has now been taken up by a wide variety of social and political sectors, when previously it was limited to certain actors directly involved in the field.

As for the progressive governments, they initially gave precedence to a “pragmatic” approach, seeking “understandings” with the heavyweights of mainstream media power; but over time, and in the heat of the political dispute in several countries, there was an opening for recognition of the Right to Communicate in the constitutional framework and specific laws. In some cases, this was the result of citizens’ action, and in others the consequence of a correlation of forces.

Nevertheless, because of the slow and limited implementation of these legal dispositions, the changes achieved remain fragile and are exposed to a permanent onslaught by media power, that is synchronized, nationally and internationally around defined strategic areas, with an overall communications offensive supported by a well-articulated network of sectors (political parties, NGOs, think tanks, academic sectors, professional bodies, etc.).

Approaches

As a backdrop to this scenario appear the difficulties in formulating communications policies and strategies, both in official spheres and in the political and social movements that seek to bring about these changes. Hence the persistence of reactive attitudes, anchored to the blueprints of the opponents, with scattered and fragmented responses dominating their action, often in a pamphleteering tone; when at the level of ideas, what is important is to confront the core ideas of the opponent, focusing mainly on the weight of one’s own arguments.

To our understanding, this is largely due to the prevalence of an instrumental view of communication that envisages it simply as a one-directional tool centred on information and dissemination, using the same models and formats defined by the powers of the dominant system. In consequence, communication is reduced to mass media and marketing (and by extension to digital networks), looking only marginally at other communicative and artistic expressions. Moreover, with this vision, the relational and dialogical component of this human activity is left aside, leading to a divorce between communication and culture.

In order to seriously analyze the course of events, it is important to recall that, for decades, adopting a standpoint critical of that approach, people’s communication (also known in English as popular or grassroots communication) has assumed that beyond just transmitting, what is important is sharing, through dialogue and participation. Popular communication therefore seeks to revive the conditions of social production and reproduction of meaning, giving particular importance to the dynamics of organization and mobilization that are central to instigating real processes of change. In the struggle for change, the ideological and cultural dispute is uppermost, since it confronts the question of hegemony; it is therefore this perspective that needs to be fostered at all levels, as a key support for effective leadership of the people in these complex times.

(Translated for ALAI by Jordan Bishop)

Osvaldo León, Ecuadorian communicologist, is director of the magazine América Latina en Movimiento.

Del mismo autor

- Desafíos para la justicia social en la era digital 19/06/2020

- La CLOC fête ses 25 ans 19/06/2019

- CLOC 25 Años 12/06/2019

- Golpe de Estado en marcha 20/02/2019

- Assembling the Bolsonaro “myth” 15/01/2019

- El montaje del “mito” Bolsonaro 21/12/2018

- Internet, derivaciones y paradojas 01/11/2018

- La mediatización de la corrupción 14/03/2018

- En tiempos de post-verdad 14/08/2017

- Comunicación para la integración 01/06/2017

Clasificado en

Clasificado en:

Comunicación

- Jorge Majfud 29/03/2022

- Sergio Ferrari 21/03/2022

- Sergio Ferrari 21/03/2022

- Vijay Prashad 03/03/2022

- Anish R M 02/02/2022